TVIRD establishes a zone of peace in Zamboanga del Norte; fosters sustainable livelihood

It was already late in the afternoon when F/B Ruaida cast off on her first fishing expedition. She slid gently toward the open sea, and at this time, one knows that night will soon set in because of the damp and cold wind hitting one’s face. The sun glowed, its reflection turning part of the sea into gold. Everybody on board savored the moment of being one with nature and communing with The Creator. Now I know why the Muslim fishermen from Sta. Maria love the sea.

Farther on, I marveled at the countryside and the ocean ahead. Maybe the town mayor was right when he claimed the place to be like paradise. But on second thought, the place is not at all just simply a place of beauty and bounty. Like the rest of Mindanao, it also has its own share of strife in the past.

Manning the wheel of the engine of F/B Ruaida is Tan Cailo, the captain of the fishing boat and the leader of his people. With his grayish-white hair and sun-burnt skin, one can tell that he is an old sea hand. His genuine smile was a cue for me to strike a conversation. I asked where we were heading and he replied that the boat – classified as a Kubkoban in the dialect – will just cruise to fish along the coastlines of Baliguian, the town next to Siocon. After all, the boat was undergoing sea-trial and this trip was simply to test whether its engine and fishing gear really worked, he added. Then he began to share snippets of his life.

Changing course

He said that he was once a rebel combatant belonging to the then potent Muslim secessionist rebel group Moro National Liberation Front (MNLF). Soon after, he and many others, returned to a peaceful life as a fisherman in Sta. Maria.

Night fell and the wind grew colder during our conversation, and all one could see was the boat illuminated by five small fluorescent bulbs while another larger, brighter light was focused directly on the waters below. Cailo interrupted our conversation with barked commands to the crew, after which the men onboard girded for action. Some carefully unfolded the large fishnet while others attended to the pulley mechanism.

“In a fishing boat like this, the most important equipment is the crew,” explained Cailo. “Therefore, a boat owner or the captain must be very kind and fair to the crew at all times; otherwise, they will leave him. How else can he catch regularly when he has no crew?” Cailo stressed.

Cailo became an elected councilman in his village inhabited mostly by Muslim Tausugs. The word Tausug means ‘brave seafarer.’ As a leader, he knew exactly that he was waging an entirely different war against the perennial enemy: poverty. Besides, he, like most of his crew, knew too that poverty was one of the reasons why he joined the rebels before.

“Without your own big fishing boat, you only get fish just enough to feed your family for a day,” Cailo said. A crewman agreed and added, “Before this, I used to fish using hook and line with a very small paddleboat. You could get four kilos at most in a day’s catch.”

The boat then slowed down and we all shared a dinner of freshly-grilled fish and hot rice with steaming coffee.

Cailo admitted that he has long dreamt of having a Kubkoban. It was the only answer to relieving his constituents from hardship and want. ”With this type of a fishing boat, you can go as far as the Sulu Seas and get a big catch. It may be costly to build but you will surely get a return on your investment in less than a year,” he explained. The Kubkoban we were on took P2.8 million to build. He said that a similar boat hauled in P100 thousand worth of fish after two days of fishing a week ago. “What if you can do that twice in a week? Then you’d be earning P800 thousand a month!” declared Cailo.

Once he convinced a wealthy relative to finance a Kubkoban venture. “I will let you run my Kubkoban. All you have to do is remit to me its profits until everything I have invested in building the boat is returned. You can have the boat after that,” said the relative. In just 6 months, Cailo was just about ready to pay the loan but had a falling out with his relative. He ended up dry and beached without a boat.

Braving new waters

At this point, the boat turned around and the crew got excited because they were ready to haul in their catch. The moment has finally arrived when the crew had to prove their mettle as fishers of the sea and for Ruaida to prove her worthiness as a fishing boat.

F/B Ruaida is collectively-owned by Tan Cailo, the crew, and around 50 other members of the Sta. Maria Fisherfolks Association, Inc. (SMFAI). In fact, they built it themselves for almost a year right after the company, TVI Resource Development Philippines Incorporated (TVIRD), agreed to make the project part of its social commitment to promote sustainable development in communities where they operate. The company operates a copper-zinc mine in Siocon but uses the Sta. Maria wharf as the port for shipping its copper and zinc concentrates to buyers. The year of construction, preparation, and anticipation reached its peak at that moment.

The boat slowed and all its lights were shut. Then a beam of light came from a small paddleboat called a banca. Cailo said the light attracts the fish milling below around the glowing lamp. Gently, the crew lowered the fishnet while the Ruaida slowly surrounded the banca until the yellow-buoyed fishnet made a circle 30-meter in diameter to trap the fish.

The lights came and the engine hummed harder. The engine below deck slowly pulled the net back to the boat with the help of the crew.

Amidst the excitement and laughter of the crew, silvery fish began to fill the boat’s deck. At first, one could count them. But as the crew pulled more, they gathered hundreds, shaking and wriggling on the deck. Eventually when the entire bulk of the net was hauled in, the flip-flopping fish formed a big mound! Prosperity was in full view with the big catch and the bigger smiles of the crew.

F/B Ruaida turned out to be a fishing boat after all. Exhausted, I slept in a corner after experiencing my first fishing expedition.

Early next morning, April 9, we steered for home. The crew was tired because of lack of sleep. Nevertheless, their smiles were as bright as the morning. In good spirits, we gathered around the grille and had our breakfast. Others were sipping coffee and smoking astern.

Close to shore

Tan Cailo reported that the night’s haul was worth P33 thousand. Not bad, considering that it was only a test run. Then he told me how he will divide the income fairly among the crewmembers. Of course, funds will be set aside for the next voyage, for maintenance, for the association, and for the required 3% plowback for the company. Fair enough, I thought.

“I can’t thank the company enough for giving us this boat. We have dreamt of this since before and now it’s here. I meant it when I said to them that this will greatly help my people. I will not fail the company,” Cailo said.

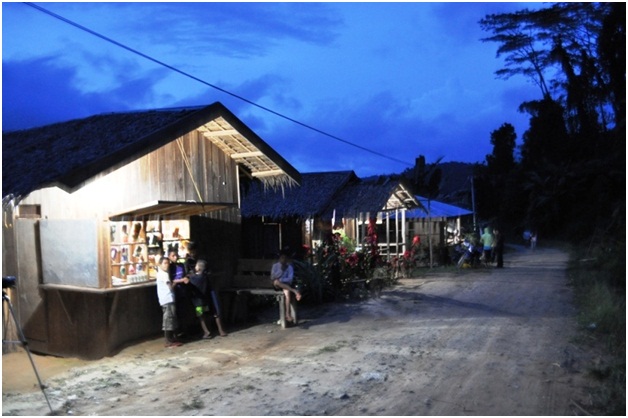

We docked near the sands of Sta. Maria, where all of the crew lived. I spent some moments chatting with the crew’s wives and children who were just as happy. I looked for Ruaida, the young woman the boat is named after. Gazing from a window was the Muslim teenager who smiles and talks willingly to a stranger, yet keeps her distance. She strikes me as a blossom in the midst of a bland, barren, and monotonous landscape of poverty. For me, she represents the village’s renewed hope for a better life.

Like the girl she is named after, the boat, too, symbolized the collective sentiment of its people: to clear the vestiges of the troubled past for peace to endure.

Postscript: Seven months after its first fishing expedition, the F/B Ruaida yielded a total gross income of P750 thousand of which P125 thousand is in the Sta. Maria Fisherfolks Association’s savings account. Meanwhile, the company has almost completed another fishing vessel project named Kubkoban 2, intended as a sustainable livelihood project for another fisher folk group comprising of former Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF) rebels. The author is a Public Affairs Officer of TVIRD, Canatuan Minesite, Siocon, Zamboanga del Norte. Before joining the company, he worked as a journalist in Zamboanga Peninsula.